A city in which everything real existed in the backstreets. Food was wok-tossed into the air and sesame, soy, and mustard hit the brain before making it to the belly. People weary from their day jobs sat down on rickety stools to have the meal of their lives. Roasted duck: an addiction. Everything seemed like it lay on the brink of existence. Life happened here in all its chaos and madness. You wanted to cling to whatever you were feeling before it vanished.

Such were the backstreets of Beijing. And they ran the show.

The shiny exterior was an edifice, a curtain. The global city was a farce. And the joke was on you if you only strolled the city on the sidewalks.

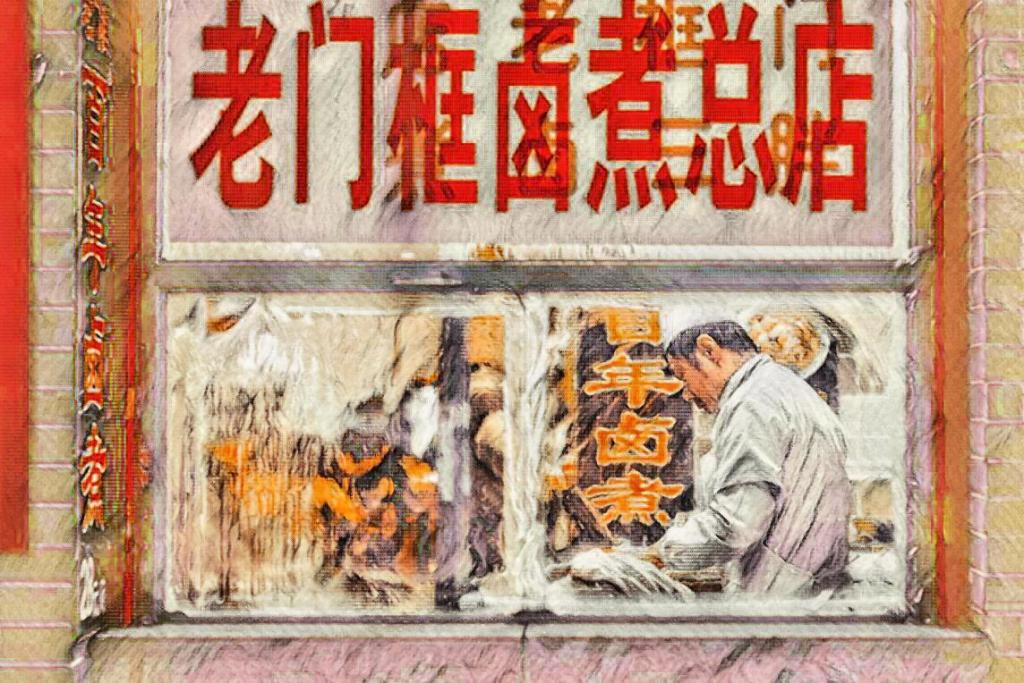

The dumpling restaurant stood at a snarky turn on Dongcheng street. It was made of old brown bamboo and was two stories tall. Run by Aunt Chen, the woman who could make a dumpling per second. “Master-cook”, they called her. To see her visage was to witness the sight of excellence and many people flood the diner to get a glimpse, to thank her for her service.

But nobody was quite lucky yet.

***

The hour hand in the mechanical clock struck five, which meant it was morning. There was no indication of sunrise because Mizu was confined to the far end of the siheyuan, meant for unmarried maids and daughters. Her quarters received the least sunlight.

Mizu hurried past the corridors knowing that Aunt Chen would be up any minute to check if her niece was on her way to the market. Today, Mizu was assigned the task of buying the duck for the dumplings.

Wearing the cloth slip-ons that Aunt Chen lent her, Mizu stepped out into dawn. With the fresh morning breeze in her face, she made her way through Dongcheng street. The grey stony structure of the walls lay silent. There were a thousand people up and about, but they all walked in peace. The peace of the morning. Only here in Beijing could so many people make no sound at all. Mizu tried to lighten her steps to not disturb the silence.

The dry feathery foliage of the Peking Willow trees fluttered as Mizu walked by, her mind mulling over the name of the place she was headed to: the Chaowai Morning Market.

On reaching the subway, she bought a card with the 20 yuan that Aunt Chen gave her and boarded the train. But when she looked around, she noticed that everyone seemed estranged and their minds were elsewhere. They were full of life when they were around people they knew. But in moments when they were left to themselves, their souls left their bodies and they fluttered like the willows.

The train soon halted at Dongdaqiao station and Mizu got off. Walking past huge piles of yellow cycles, crossing streets buzzing with the humdrum of people on their way to work, she finally reached the market.

The previous night, Aunt Chen described the duck shop with much precision, relying little on Mizu’s own discernment. “White signboard. Red letters. Selling duck and only duck.”, recalled Mizu. She understood why her aunt had chalked down the details. The market extended before her in an unending line of stalls. Meat, eggs, shiitake mushrooms, leaks, and freshly made noodles, everything used in the Chinese cuisine was on sale. The air was rife with the aroma of spices and the voices of cheery hawkers with smiles fresher than their produce. But Mizu cut through the crowd and headed straight to the store with the signboard.

She bought five portions of duck, thanked the shopkeeper, and walked away secretly taking in all the wafting aromas of the 100 different sesame sauces and chili pastes. She headed back to Aunt Chen’s restaurant where her presence was expected before 6 o’clock.

***

The morning passed quickly. The duck was washed, minced, marinated, and cooked. The dough was folded, rolled, and cut. 10000 dumplings were steamed and fried and by 12 pm the doors to ‘Aunt Chen’s Noontime Diner’ were opened.

It served the juiciest dumplings in the world with the thinnest dough and a sesame oil dressing that could intoxicate. The regular customers were businessmen and women, young and old – Beijing’s inmates who knew where to find the good cuisine, a chosen few who knew the city like the back of their hand. Unruly school kids visited too and Mizu would sneak an extra bowl of soup with their order.

Mizu had been here for two long months. Helping Aunt Chen out to reopen her business and earning a decent weekly wage for the same. At the restaurant, the two women were free. Chinese choir music played on the radio, smiles were borrowed and exchanged, and fragrant pots of food stirred endlessly in the kitchen.

At home it was different. Uncle Wen ran the siheyuan like a guardhouse. The women were confined to their rooms and were forbidden to read or write. Only the housemaids, vicious Uncle Wen, and now Mizu had seen Aunt Chen’s face after she was married.

With Mizu at home, however, Aunt Chen enjoyed some freedom. The freedom of waking up early and prepping for the restaurant. When Uncle Wen lost his job, it was only Aunt Chen’s dumpling diner that could save them from going bankrupt. He had no choice but to let go of the reigns. Once, Aunt Chen revealed to Mizu that she would rather go into debt as it would mean selling the godforsaken house. But Uncle Wen wouldn’t lose the only thing that gave him some sense of authority, thought Mizu.

Aunt Chen would often narrate stories over leftover dumplings with Mizu. “This recipe comes from my māma. She would go all the way to Xiushui Market to get the soy sauce. She knew a lady there that fermented it for 40 years. ”, said the aunt animatedly.

“Uncle Shiu once visited the Great Wall where he saw people stealing bricks to sell them at the nearby market.”, said her aunt on another day.

Aunt Chen had many tales to tell, but she was never in them. She had lived vicariously through others. Mizu had to get her out into the city. She was leaving Beijing tomorrow and she was determined to take Aunt Chen someplace.

***

The next day, by seven o’clock, Mizu and Aunt Chen finished prepping for the restaurant. The maid Siutzen was left in charge of evading Uncle Wen as she was the only one who could be trusted.

“So, where are we going? There’s the Forbidden City and the Great Wall…”, asked Mizu, wearing her cloth slip-ons.

“To Beihai Park”, interrupted Aunt Chen.

“A park?”, exclaimed Mizu. But Aunt Chen was resolute and didn’t respond to her niece.

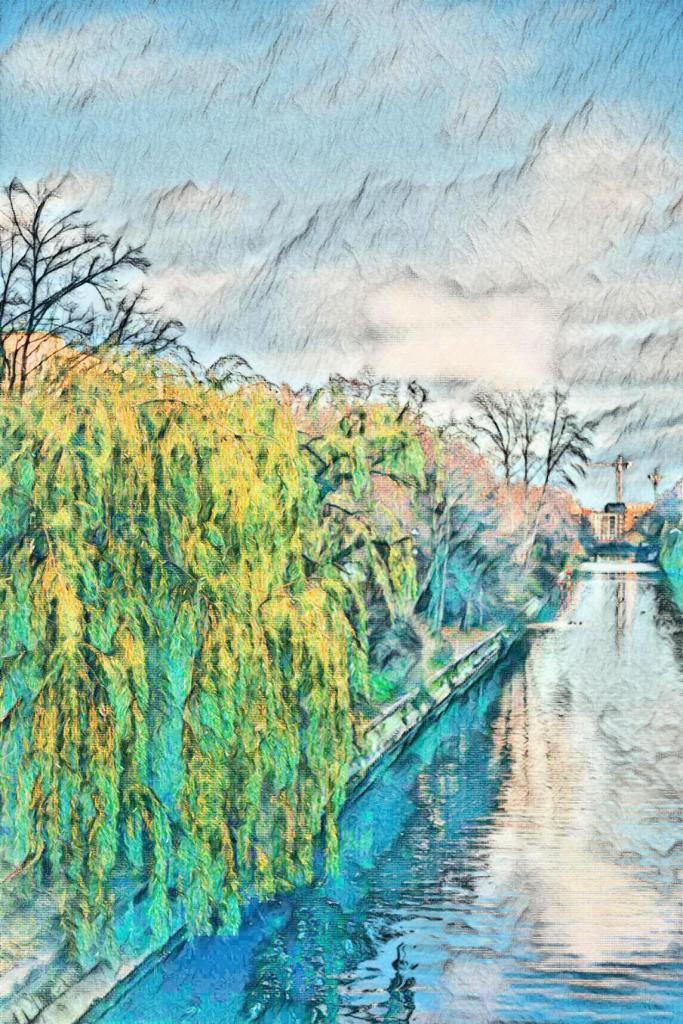

When they reached Beihai Park, one thing was certain, it was a vivid place. Locked away in time. The wind rustled the leaves and the birds chirped and then there was silence despite it all. Boats slowly floated down the river as if they were leaves. There was silence despite sound. As if somebody somewhere was orchestrating every second of the scenery in front of them. A white pagoda, 131-foot in height, marked the sky at a distance, but seemed to float away whenever the clouds passed.

Aunt Chen was weary working behind the curtains, in the backstreets. She wanted to see the light, to witness what Beijing had become. The city took off and left her in an inescapable void, like the sunlight-ridden chambers of the house she lived in. Now in the warm comforting glow of the morning light, she felt the presence of time, of time that passes and changes all things.

Mizu found a spot by the river and put down a blanket. Aunt Chen began reading to her from a book of poetry by Jia Dao who wrote about white clouds and monks in recluse on the mountains. Serenity. Peace. This is where the inmates of Beijing got their silence from. Looking at the lake before her, Mizu thought of the city. She hadn’t toured it, but had experienced it through the life of Aunt Chen.

“China had many matriarchs. Until Confucius and Mencius wrote in stone that men and women were not equal. It is heaven-ordained, they said, that man should be in power”, Aunt Chen had told her.

Beijing had culture, had grace, had poetry, but its inmates were seldom free. And is art that restricts, art at all? The exterior was beaming superficially, ornamented by heritage, and the interiors were tangled, rotten, and distorted. They were real, but at what cost? Mizu looked at Aunt Chen and thought about her face, a face that only a handful of people had associated with her name which meant “morning”.

Aunt Chen took out a wooden box from her bag and offered it to Mizu. They shared sesame dumplings looking at the Peking Willow trees before them in Beihai Park. How they swayed in the breeze here, how different they looked from the ones on the backstreet.

The next city takes us towards the coast!

Dumpling is my favourite! I can get the feel of Beijing! Beautiful pictures or photos?

LikeLike

In this particular post, they are photos. I paint too, sometimes, when I need to visually represent an emotion. Thankyou, Chen Song Ping 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person